Burma today is one of the most devoutly Buddhist countries in the world. Though there is no official state religion, 89% of Burmese people are Theravada Buddhists, nearly every Burmese man spends a few weeks of his life in a monastery, and anybody who is perceived to have insulted Buddhism (inadvertently or not) can face jail. Given all this, you’d be forgiven for assuming that Buddhism was the only religion in Myanmar – but you’d be wrong. Burma actually has a strong tradition of indigenous religion – or nat worship – and it’s alive and well today.

It’s thought that Buddhism first arrived in Burma from India in the third century BC, but it didn’t really catch on in earnest until the 11th century, when the empire-builder King Anawrahta was converted to Theravada Buddhism by a Mon priest. Under him, Burma saw a cultural flowering unmatched at any time before or since, and magnificent red-brick temples sprung up across the central plains.

But while all of this was happening, an even older religious tradition was bubbling away beneath the surface – and no matter hard anybody tried to stamp it out, it refused to be silenced.

Nat worship

Practitioners of nat worship believe that everything in the world is governed by nats, or spirits. Places, people, trees, rocks and areas of life are all associated with particular spirits – and not all of them benign. Nats can guard and protect, but they can also be mischievous and vengeful, and some even have the power to possess people and force them to do their bidding. These types of nats require offerings to keep them sweet, and Burmese people will often leave out food and other gifts to placate them.

Myths & legends

Nat worship is not a formal religion, which means there are all kinds of different beliefs and traditions spanning the different regions of Burma. Some nats are analogues of gods from Hindu mythology or the ghosts of historical figures, but most are simply the vengeful spirits of people who died particularly bloody and violent deaths.

All this variety makes for a particularly colourful canon of stories – such as that of the nat Ouktazaung, who lures men with a siren-like call and takes them hostage so she can roam free on the earth in their place, or the nats Min Mahagiri and Hnamadawgyi, who hide in trees and devour anybody who comes near.

The creation of the nat pantheon

Before King Anawrahta came to power in the 11th century, nat worship was the main belief system of Burma, but there was no pantheon to speak of. At first, Anawrahta tried to ban nat worship, ordering the destruction of all shrines and statues relating to it, but his subjects simply replaced their family statues with coconuts and carried on regardless. At this point, Anawrahta shrewdly decided that if you can’t beat ‘em – join ‘em, and set about moulding nat worship into a shape that would fit his own religious notions.

This meant formalising all existing nats into a pantheon of 37, and placing one – whom he renamed Thagyamin – at its head. This king of the nats incorporated elements of both the Hindu deity Indra and the Buddhist deva Sakra, and thus slotted rather nicely into the wider Buddhist tradition that soon subsumed nat worship in Burma.

Traditions and worship

King Anawrahta set the course of nat worship for the next millennium, and today you’ll find nats routinely worshipped alongside Buddhism in Burmese homes. Indeed, if you know where to look, signs of nat worship are everywhere: a red-turbaned coconut in a local home, a white-and-red cloth tied to a rear-view mirror, or a small shrine under a tree – these are all evidence of nat traditions.

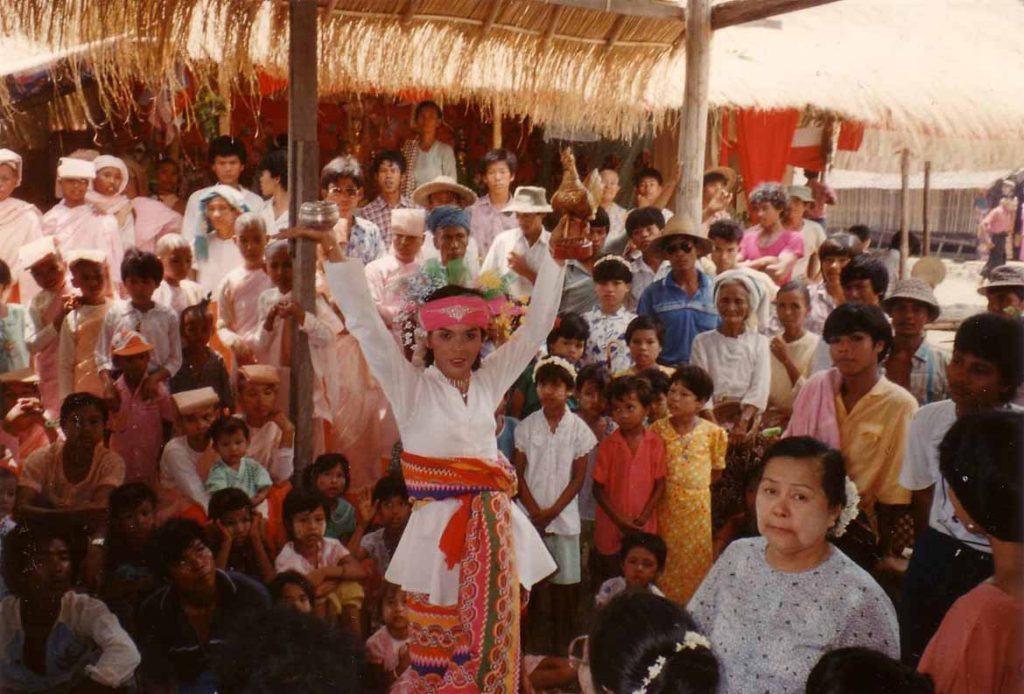

Though less common in urban areas, nearly every village in Burma has a nat sin – a shrine to the village guardian nat – and many people still burn incense to appease Min Mahagiri, the home guardian nat. Places where nat worship is strong will also have a nat kadaw – or spirit medium – who acts as a focal point for local festivals (nat pwe) and channels the spirits through trances.

Interestingly, as nat kadaw are considered to transcend traditional gender boundaries, the profession has become something of a refuge for transgender Burmese, who would otherwise struggle to find acceptance in conservative Burmese society. Read more about this here.

See nat worship today

If you’re interested in learning more about Burma’s indigenous spirit-worship, there’s no better place to visit than Mount Popa. This sacred temple, which sits atop a striking rock formation overlooking the plains, is the most important centre for nat worship in the whole of Burma – and makes a very easy day trip from the temples of Bagan.

Our Beautiful Burma group tour includes a visit to Mount Popa with a local guide, who will be able to tell you all about the tradition of nat worship in Burma. If you’d like to learn more, get in touch!