It is a sad fact that some of the most elegant and impressive architecture in Burma is the legacy of colonisation. Promoting colonial Burma and its heritage is problematic: can you celebrate the achievements of an exploitative regime without implicitly celebrating the regime itself? Is it right that we should evoke romanticised images of the glories of Empire to inspire modern travellers to Burma?

The travel industry shouldn’t shy away from these issues. Responsible tourism depends on awareness of and sensitivity to historical context, and the colonial history of Burma absolutely should be remembered. Like Cambodia’s Killing Fields or Vietnam’s Cu Chi Tunnels, the relics of Burma’s colonial past exist as reminders of an episode of history that must never be repeated – they should not be erased or ignored, lest they be forgotten.

Apart from anything else, if we avoided or demolished every monument constructed by a society renowned for its exploitation of other human beings, we’d have to level most South American cities, knock down the pyramids, demolish Angkor Wat and the Taj Mahal, and get rid of basically everything in Europe… there wouldn’t be much left of the glories of human industry, let’s put it that way. We need these monuments to mankind’s former mistakes.

Burma’s colonial history in a nutshell

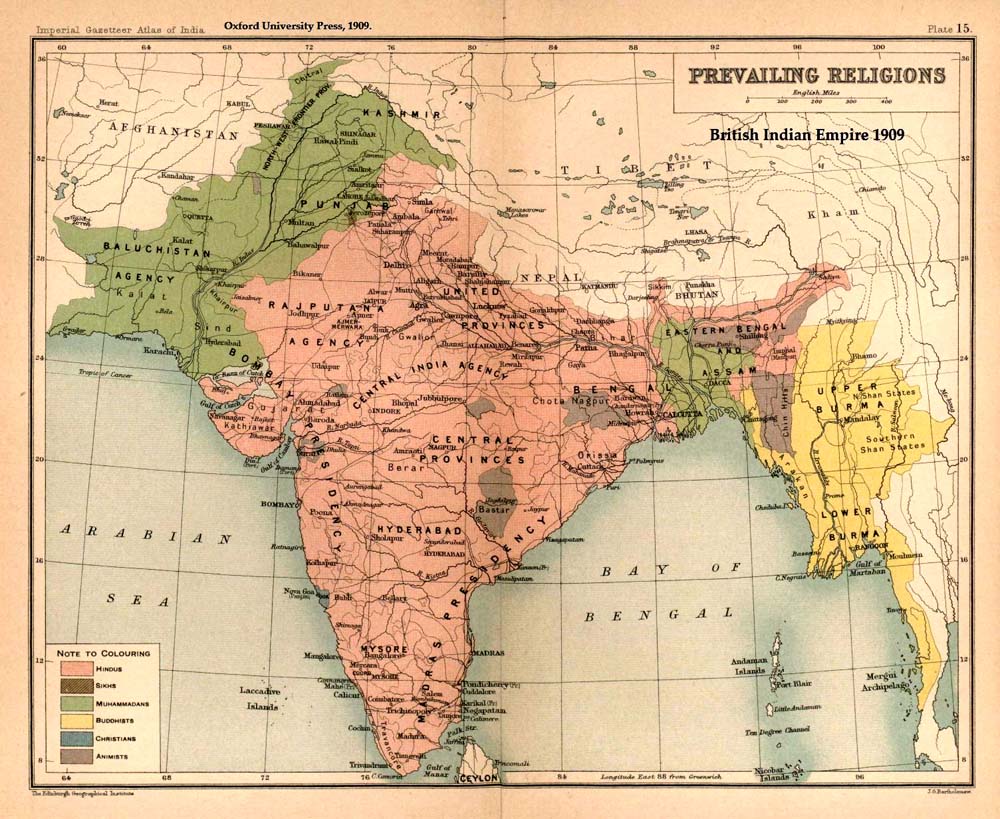

British rule in Burma began in 1824. Advancing piece by piece over the course of three hard-fought Anglo-Burmese wars, the British officially assumed power over Burma in 1886, making it a province of British India and establishing a new capital at Rangoon (present-day Yangon).

British rule in Burma heralded dramatic changes within Burma’s society and economy. The monarchy was abolished, farming was expanded to cater to international demand, religion and state were officially separated, all of which led to massive, nationwide upheavals. Burma’s wealth increased, but it was concentrated in the hands of the British; not of the Burmese.

Unrest grew from the beginning of the 20th century. Strikes and protests had escalated into armed rebellion by the 1930s, and in 1937 the British officially separated Burma from India – granting it a new constitution, a fully elected assembly, and a Burmese prime minister. This did not placate the Burmese public, who saw it as an attempt to exclude Burma from more dramatic reforms currently taking place in India. Violent clashes between British police and Burmese protesters – mainly university students – persisted.

The Second World War changed everything. The celebrated Burmese revolutionary, Aung San, allied himself with the Japanese in the hope of using this relationship to wrest control from the British – but the Japanese took advantage of this trust to invade and subjugate Burma. Pushed back to the British, Aung San joined the Allied forces, ousted the Japanese from power, and finally negotiated independence from Britain in 1947.

Five ways to relive colonial history in Burma

1) Join a Yangon colonial heritage walk

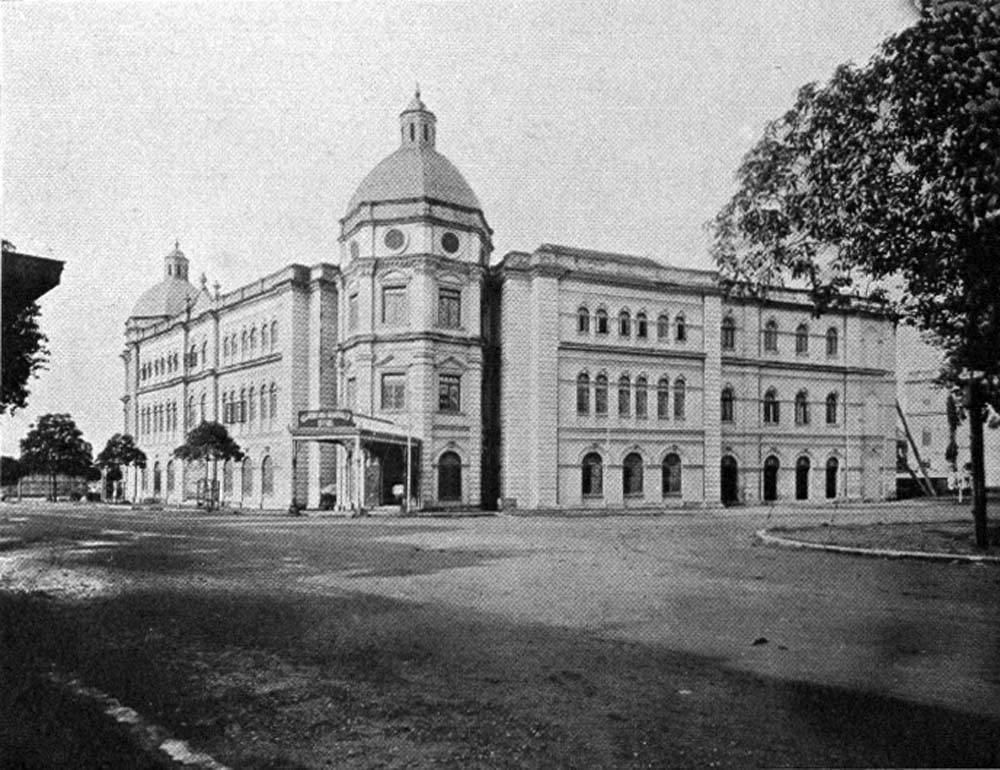

A walking tour of Yangon, erstwhile capital of British Burma, provides the perfect introduction to the country’s colonial history. With a knowledgeable guide on hand to provide all-important context, this tour introduces one of the most impressive collections of colonial-era architecture in Asia, including visits to City Hall, the old railway station, St Mary’s Cathedral and the former minister’s office where Aung San was finally assassinated. The walking tour includes high tea at the Strand Hotel, which should certainly be a highlight!

2) Take a train ride across the Goteik Viaduct

In the hills of western Shan State, forming a bridge across a vast gorge between Pyin Oo Lwin and Lashio, is the Goteik Viaduct. Completed in 1900 by Pennsylvania and Maryland Bridge Construction, it was the largest railway trestle in the world at the time of its completion – and remains the highest bridge in Burma.

Today, trains still trundle slowly across the vertiginous viaduct on their way through Shan State, giving passengers a jelly-leg-inducing, 689-metre (2,260 ft) stretch above a 250-metre (820 ft) sheer drop. The views, as you might expect, are incredible.

3) Float along the “road to Mandalay”

Forever imprinted in the romantic imagination thanks to Kipling’s famous poem, the “road to Mandalay” refers to the great Irrawaddy River, which served as the means of transport for British troops during Kipling’s time. The original Irrawaddy Flotilla Company, which began operating in Burma in 1865 and was at one time the largest fleet of river vessels in the world, still runs trips along this mighty waterway, allowing visitors to travel in elegant, colonial-style vessels lovingly restored and finished in teak and brass.

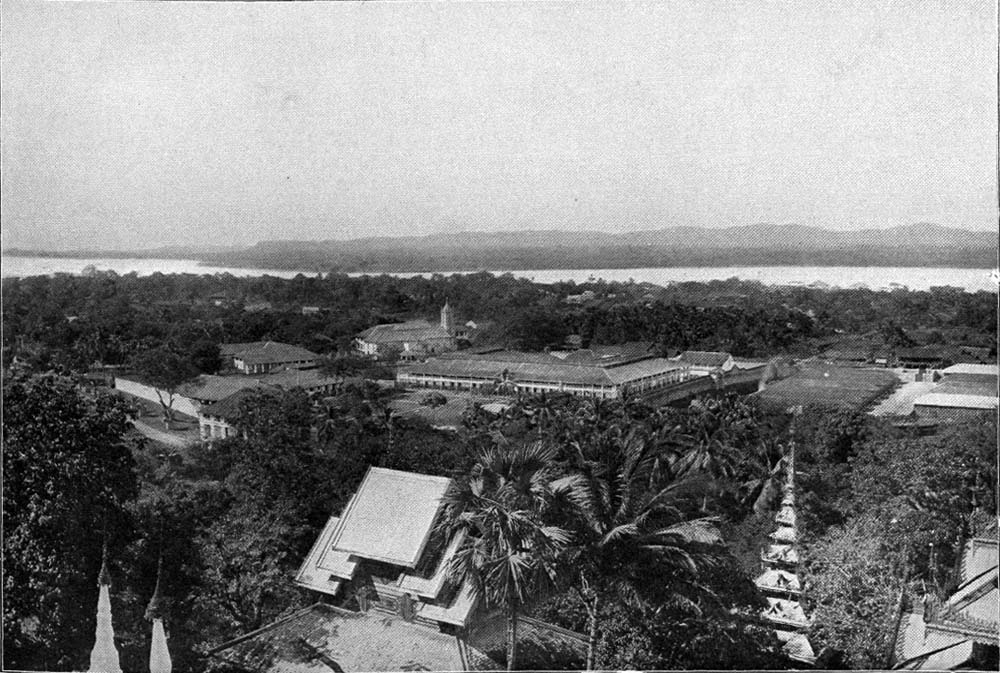

4) Follow in the footsteps of Kipling and Orwell in Mawlamyine

Of all Burma’s former colonial outposts, Mawlamyine (formerly Moulmein) is one of the best-preserved and most atmospheric. The capital of British Burma from 1826 until 1852, George Orwell lived here for a time (his autobiographical essay “Shooting an Elephant” was set here), and the city is home to Kipling’s famous “Moulmein Pagoda” (Kyaikthanlan Paya). With fewer tourists than the more famous locales of Yangon and Mandalay, this is the perfect place to rediscover the atmosphere of the Raj.

5) Visit the colonial hill station of Pyin Oo Lwin

Located in the hills of Shan State, Pyin Oo Lwin was a quiet Danu village until it was discovered by the British in 1896 and developed into a popular summer retreat for the colonists. The town was renamed “Maymyo” (May’s Town) after the British colonel James May, a railway constructed from Mandalay, and Edwardian-style summer cottages built for the comfort of the summer administration.

Today, Pyin Oo Lwin continues to provide a respite from the sweltering summer temperatures of the lowlands, and seems almost like a slice of 1920s Britain transplanted into the highlands. One of its best attractions are the botanical gardens, established by Alex Roger in 1915 and modelled after Kew Gardens in England.