As tourism in Burma gathers pace, the number of travellers visiting the plains of Bagan and the city of Yangon are gradually increasing. But Violet finds a quiet corner of the country that remains relatively unexplored, despite being just as impressive as protected heritage sites in other countries.

Monywa

Monywa is one of those places that makes you realise just how much there is to discover in Myanmar beyond the famous tourist sites.

An unassuming little town roughly mid-way between Bagan and Mandalay, Monywa rarely features on itineraries – and in fact, most visitors leave Myanmar without ever having heard of it. Yet for such a little-known destination, it packs a fantastic punch. Historic sites, great hotels, excellent restaurants, an interesting night market and a healthy dose of Burmese weirdness: Monywa’s got the lot, and makes a fantastic addition to the traditional route through Burma.

Laykyun Setkyar

Take the Laykyun Setkyar, for instance. If you’ve ever heard of Monywa at all, it’ll be because of this monster of a statue: 116 metres of burnished, golden Buddha, towering incongruously over the plains since 2008. Then there’s nearby Thanboddhay Pagoda (one part Buddhist temple; several parts wedding cake), a front-runner for oddest place in Burma and a very interesting spot to pass an hour or two.

All of these things on their own would make Monywa a worthy stop on any trip, but in my opinion, its most interesting and underrated attractions of all are the wonderful caves of Po Win Taung and Shwe Ba Taung, which I visited in May this year.

Po Win Taung

Po Win Taung (also variously spelt Pho Win Taung and Po Win Daung) is one of Burma’s most important historic sites – and yet almost nobody has heard of it.

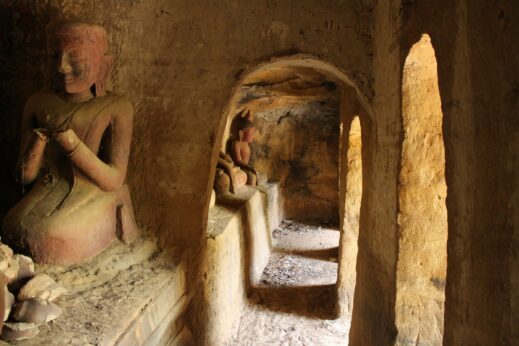

The third-biggest archaeological site in Myanmar after Bagan and Mrauk U, Po Win Taung consists of hundreds of man-made caves carved into sandstone across the hillsides, and is thought to have been constructed over hundreds of years, beginning in the 14th century and concluding as late as the 18th century. According to legend, it’s also home to a massive 444,444 Buddha images – though the true number is probably closer to 4,000 (and I’m afraid I didn’t stop to count them).

Though the scale of the thing is impressive, Po Win Taung’s interior murals are its main attraction. These depict Buddhist mythology and Burmese daily life in intricate and beautiful detail, and some claim they represent the largest collection of rock paintings in the whole of Asia – making it all the more surprising that so few visitors make it here.

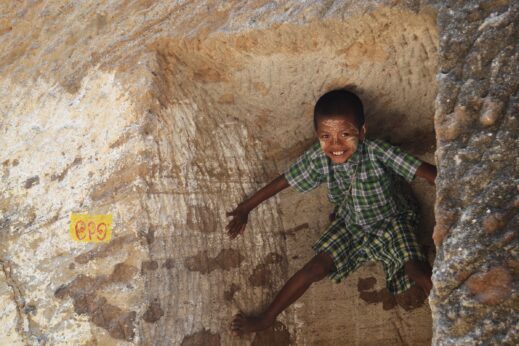

It reminded me very much of China’s stunning Mogao Grottoes – but without the ugly architectural ‘improvements’, the hordes of tourists, and the monumental entrance fees. Just watch out for the pesky macaques – they’re the ones who are really in charge here!

Shwe Ba Taung

Shwe Ba Taung is Po Win Taung’s younger – and to me, even more impressive – neighbour.

Here, masons working in the late-19th and early 20th centuries dug straight down into a flat outcrop of rock, creating a series passageways and staircases up to ten metres deep in the cliffside.

Where Po Win Taung features simple facades with little ornamentation, Shwe Ba Taung’s excavated caves are flanked by huge, ornately carved doorways, some a full six metres tall, and all painted in bright pastel colours. It is these great doorways that have earnt the site comparisons with Jordan’s Petra and Ethiopia’s Lalibela – but what really makes them fascinating is their unusual fusion of colonial influence and native design.

Everywhere are elaborate columns, architraves and cornices inspired by neo-classical architecture, and each door is decorated with an array of motifs borrowed from European design. Some facades, for instance, feature the coat of arms of Great Britain (it’s thought that the British had a hand in construction), while others are decorated with clock motifs thought to have been inspired by Italian glassmakers in Mandalay. Mixed in with these occidental elements, meanwhile, are more typically Burmese symbols: parasols, peacocks, elephants, tableaux from Buddhist mythology – even a couple of cheroot-smoking cherubs.

It’s an irreverent fusion of styles found nowhere else in Burma, and though the murals may be less intricate and beautiful than at Po Win Taung, to me the overall effect is even more impressive.

Getting there

Monywa is conveniently located between Bagan and Mandalay, with numerous daily buses and shared minibuses heading in both directions. Shwe Ba Taung and Po Win Taung lie next-door to one another, about an hour and thirty minutes’ tuk-tuk ride from Monywa town. Pay a little more for a car and you’ll get there quicker. Entrance fees are 2,500 kyat per site – which is a steal!

It’s possible to explore Po Win Taung at your leisure, but it’s such a vast network that you’d be wise to enlist a guide to show you to the most beautiful caves. There should be plenty of locals about to offer their services. Shwe Ba Taung is less extensive, and can easily be explored without a guide.

All of Monywa’s sights can be tackled in a day, but for a more leisurely option, we recommend spreading them out over two days. This should give you plenty of time to explore Monywa’s riverside and lively night market, and to enjoy its excellent restaurants.

Travel to classic highlights Mandalay, Yangon and Bagan as well as the lesser-travelled Andaman islands, Kengtung and Monywa on our Untouched Burma itinerary.